Healthcare Provider Update: Healthcare Provider Information for Aetna Aetna, part of the CVS Health family, has been a key player in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace, providing health insurance plans to individuals and families. However, significant changes are on the horizon for 2026, as Aetna will exit the ACA marketplace in 17 states, impacting approximately 1 million members. This withdrawal is attributed to the company's challenges in maintaining competitiveness and providing value in a rapidly evolving healthcare landscape. Potential Healthcare Cost Increases in 2026 As the healthcare landscape shifts, substantial premium hikes are anticipated for those enrolled in ACA marketplace plans, with projections of up to 75% increases in out-of-pocket costs due to the potential loss of enhanced federal subsidies. In some states, insurers have filed for rate increases exceeding 60%, driven by surging medical costs and the expiration of premium tax credits established under the American Rescue Plan. For Aetna's former members, this change further complicates their healthcare landscape as they seek new insurance options amid heightened financial pressures. Click here to learn more

Table of Contents

When Stock Prices Are High What You Can Do With Dca

Prologue

The majority of Aetna employees we talk to bring up the difficulties of investing. Uncertainty is a constant in investing. Recent bias makes the current time, whenever that may be, feel more uncertain than ever. The COVID-19 pandemic and modern conflicts presented us with truly unprecedented economic and health-related uncertainty, but stepping back to any point in history there is always a reason that this time is different; this is true in both bull and bear markets. Uncertainty is not necessarily a bad thing - if investing felt certain we would not expect to collect a meaningfully positive risk premium from owning risky assets. For long-term investors, stocks should deliver on their positive expected returns. The concept of hanging on through tough markets to benefit from long-term expected returns is relatively easy for most investors to understand. The tricky part is doing it, and it doesn’t get any trickier than making the decision to invest a lump sum of cash.

The nagging uncertainty that comes with investing in the stock market seems to be particularly pronounced when it comes to investing “new money.” New money could be a windfall from selling a home or business, receiving an inheritance, or winning the lottery. Whatever its source, shifting from cash into stocks can be a nerve-racking experience. In the case of new money, it doesn’t help to know that long-term expected returns are positive when you are deciding to invest a large sum at a single point in time. Instead of investing a lump sum all at once, you might choose to enter the market gradually over some pre-determined period. This is commonly referred to as dollar-cost averaging. It seems intuitive that dollar cost averaging would lead to a better average outcome. You are buying more stocks when stocks are down and less when they are up, and you are avoiding the potential timing error of investing right before a crash. As usual, intuition and investment decisions don’t mix.

This paper aims to compare dollar-cost averaging (DCA) to lump sum investing (LSI) through time for Aetna employees and retirees. We will examine average historical outcomes, the worst LSI outcomes, historical bear markets, and historically expensive markets. Neither this analysis nor its broad findings are new. A 1979 paper in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis by George Constantinides, A Note on the Suboptimality of Dollar-Cost Averaging as an Investment Policy, regards DCA as suboptimal through two propositions. A 2012 paper from Vanguard, Dollar-cost averaging just means taking risk later, found that LSI beats DCA about two-thirds of the time in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

This paper extends the analysis to include a closer look at the distribution of outcomes on average and under special circumstances commonly believed to be suboptimal for LSI.

Overview

Many Aetna employees and retirees have told us how difficult it feels to evaluate certain investment strategies. To evaluate DCA as an investment strategy we will compare it to lump sum investing for rolling 10-year investment periods with monthly steps. This means that starting with the first available month we will examine DCA and lump sum investing through the following decade of returns, and then move the start point one month ahead. For most data series in our sample, this results in 485 10-year periods. For Canada, we have 652 periods, and 1013 for the US. We will evaluate a 12-month DCA implementation, which means splitting up a lump sum into 12 equal monthly investments, against a single lump sum investment. The following chart shows an approximate allocation between cash and stocks over the course of a 12-month DCA period for $1,000,000 of starting cash.

Figure 1 – Dollar-Cost Averaging Illustration

Source: Benjamin Felix, Portfolio Manager, PWL Capital Inc.

In our model, the cash will earn interest at the rate of One-Month US Treasury Bills while it is waiting to be invested. The portfolios are 100% invested in stocks when fully implemented. All analysis has been conducted in US dollars using monthly returns for One-Month US Treasury Bills and the six global stock markets listed in Table 1.

Table 1 – Stock Market Indexes

Source: Benjamin Felix, Portfolio Manager, PWL Capital Inc.

In order to evaluate LSI relative to DCA, we have chosen to look at the ending performance of an investment after 10 years. First, we evaluated the full data series for each market to understand the average outcomes. We isolated the most extreme bad outcomes for LSI to examine how DCA performed in those periods. Knowing that we cannot predict when LSI will have its worst outcomes, we then compared LSI to DCA during bear markets and when stock prices are high.

The Properties of Stock Market Returns

The equity risk premium – the premium that stocks are expected to deliver over a risk-free asset – tends to be consistent over long periods of time. Using US stock data going back to 1926 we can observe the nature of the premium.

Featured Video

Articles you may find interesting:

- Corporate Employees: 8 Factors When Choosing a Mutual Fund

- Use of Escrow Accounts: Divorce

- Medicare Open Enrollment for Corporate Employees: Cost Changes in 2024!

- Stages of Retirement for Corporate Employees

- 7 Things to Consider Before Leaving Your Company

- How Are Workers Impacted by Inflation & Rising Interest Rates?

- Lump-Sum vs Annuity and Rising Interest Rates

- Internal Revenue Code Section 409A (Governing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans)

- Corporate Employees: Do NOT Believe These 6 Retirement Myths!

- 401K, Social Security, Pension – How to Maximize Your Options

- Have You Looked at Your 401(k) Plan Recently?

- 11 Questions You Should Ask Yourself When Planning for Retirement

- Worst Month of Layoffs In Over a Year!

- Corporate Employees: 8 Factors When Choosing a Mutual Fund

- Use of Escrow Accounts: Divorce

- Medicare Open Enrollment for Corporate Employees: Cost Changes in 2024!

- Stages of Retirement for Corporate Employees

- 7 Things to Consider Before Leaving Your Company

- How Are Workers Impacted by Inflation & Rising Interest Rates?

- Lump-Sum vs Annuity and Rising Interest Rates

- Internal Revenue Code Section 409A (Governing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans)

- Corporate Employees: Do NOT Believe These 6 Retirement Myths!

- 401K, Social Security, Pension – How to Maximize Your Options

- Have You Looked at Your 401(k) Plan Recently?

- 11 Questions You Should Ask Yourself When Planning for Retirement

- Worst Month of Layoffs In Over a Year!

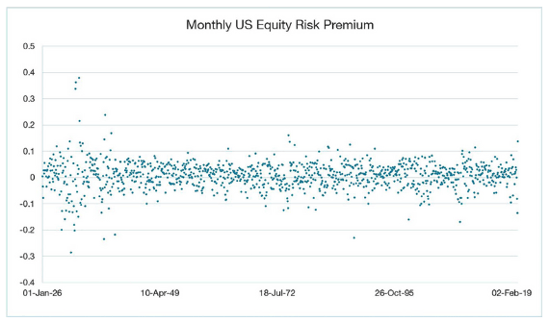

Figure 2 – Historical Monthly US Equity Risk Premium

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, PWL Capital Inc.

The monthly US equity premium has been remarkably consistent, within a range, throughout history. It has an arithmetic average of 0.65%, and it has been positive 60% of the time. There tend to be periods, visible in Figure 2, where the monthly premium becomes more volatile; volatility clustering is a well-known phenomenon. Over periods longer than one month we also observe characteristic negative skewness - frequent small gains and a few extreme losses.

Given the nature of stock returns, we would expect a stock investor to achieve positive returns with roughly the same frequency as the equity risk premium being positive. For the remainder of this paper, we will be comparing lump sum investing to dollar-cost averaging in terms of absolute returns, as opposed to observing their risk premiums. US stock returns have been positive in absolute terms 63% of the time in the historical data.

Average Lsi Vs. Data Results

For most markets, and on average across markets, we find that roughly two-thirds of the time LSI beats DCA over 10-year periods in terms of ending assets. The exception is Japan which is unsurprising given its unique long-term stock market outcome; Japan’s equity market has trailed One-Month US Treasury Bills since 1990.

Table 2 – LSI vs. DCA for 10-Year Historical Periods

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices, PWL Capital Inc.

The basic insight that we draw from this result is that, on average, LSI leads to greater ending wealth than DCA. To quantify the extent to which LSI tends to beat DCA we examined the 10-year annualized performance difference for the full sample. An annualized figure stated as a percentage makes for an easy comparison to familiar items like fees and withholding taxes. On average, DCA is leaving a meaningful amount of expected returns on the table at 0.38% annualized over ten years in the historical data; this should not be a surprise considering that DCA delays exposure to higher expected returning stocks.

Table 3 – LSI vs. DCA Annualized 10-Year Performance Difference

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices, PWL Capital Inc.

Comparing average outcomes is interesting but it does not speak to the dispersion of outcomes. Even if DCA is worse on average in terms of expected average outcomes, maybe it offers some protection on the downside. To assess this, we calculate the difference in annualized returns for LSI and DCA over 10-year periods and sort the data into percentiles. The 10th percentile is the bottom 10% of outcomes, the 50th percentile is the median, and the 90th percentile is the top 10%.

Table 4 – Difference in Annualized Returns (LSI – DCA)

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices, PWL Capital Inc.

It should be clear from Table 4 that LSI is beating DCA by a healthy margin on average. In the best 10% of outcomes (90th percentile), more has been gained by LSI over DCA than what has been lost in the worst 10% of outcomes. The median outcome is positive, and the distribution is negatively skewed. None of this should be a surprise considering the positive expected risk premium of stocks over treasury bills, and the left-skewed distribution of stock returns. Figure 3 shows the shape of the distribution of the differences in outcomes for LSI less DCA in terms of 10-year annualized returns.

Figure 3 – Distribution of Differences in 10-Year Annualized Outcomes (LSI - DCA)

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices, PWL Capital Inc.

At the most extreme, the far left and right tails of the distribution, LSI does look worse than DCA. This observation is consistent with a negatively skewed distribution; we see that most of the outcomes are good, but the worst outcomes are more extreme than the best outcomes. This validates the idea that DCA might be able to offer protection from the worst outcomes, but it comes at a significant cost in terms of expected returns.

Lsi Tail Findings

Average historical outcomes may be of limited psychological value when making investment decisions under conditions of uncertainty. An investor doesn’t necessarily care to know about average outcomes – any point in time will never feel average to those living in it. Investors want to minimize their perception of the downside risk associated with investing a large sum of cash in an uncertain market. It is important for Aetna employees to note that this exercise is distinct from examining the percentiles in Table 4. Table 4 demonstrates the distribution of differences in outcomes. That is the magnitude of the average performance difference between LSI and DCA across the full data set.

Sorting by the difference between LSI and DCA lets us think about the total distribution of outcomes for DCA relative to LSI, but we are now interested in how DCA does when LSI does poorly relative to the full set of LSI outcomes. To examine this, we sort historical outcomes by LSI ending assets and observe how DCA performs when LSI has its worst 10% of historical outcomes. Framed differently, if we knew that the next 10 years would be among the worst in history for a lump sum investment, could we count on DCA to improve the outcome?

Table 5 – LSI vs. DCA in the 10th Percentile LSI Historical Periods

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices, PWL Capital Inc.

In half of our markets, LSI still beats DCA most of the time even when LSI has delivered its worst historical outcomes; this is also true with an equal-weighted average of all markets in the sample. The results are not as strongly in favor of LSI as the full data series but remember that we have intentionally selected the worst LSI outcomes for this sample. While the number of outcomes is evenly matched, the bad outcomes in this case are worse in magnitude than the good ones. The result is a negative difference in annualized 10-year performance. This should not be surprising considering our intentional selection of the worst LSI outcomes in the sample.

Table 6 – Difference in Annualized Returns for 10th Percentile LSI Outcomes (LSI – DCA)

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices, PWL Capital Inc.

Even under artificial conditions of a known bad future outcome for LSI, DCA offers less than a 50% shot at an improvement. DCA does however offer an edge when the magnitude of positive and negative outcomes is considered – despite the roughly even split between good and bad outcomes, the bad outcomes are worse than the good outcomes are good. This seems to give credence to the mythical ability of DCA to improve an extremely bad LSI outcome. An important nuance in the data is that the worst LSI outcomes relative to other LSI outcomes do not correspond with the worst LSI outcomes relative to DCA outcomes. The most extreme instances of underperformance for LSI relative to DCA have less to do with the LSI outcome being extremely bad and more to do with the DCA outcome being extremely good. In other words, lucky timing for DCA, as opposed to avoiding unlucky timing for LSI, drives the difference in the most extreme cases.

Given that it is impossible to predict which time periods will result in the worst outcomes for a lump sum investment, we next turn to two signals commonly believed to offer forward-looking insight into future investment returns.

Utilizing Dca in Bear Markets

One seemingly obvious case where DCA feels like it should shine is during bear markets - market drops of 20% or more. Stock market volatility tends to cluster; when markets are turbulent, they tend to remain so for some time. Spreading an investment out over 12 months in the face of a bear market seems like a reasonable approach to improving the expected outcome. To be clear, we are assuming that the 20% drop has already happened when we are making the LSI or DCA decision.

For this sample, we have defined a bear market as a monthly drop of 20% or more from the previous peak. We will begin the LSI and DCA samples in the month following the drop, with the idea being that an investor with new cash has just observed a 20% or greater drop in the market and is now deciding between LSI and DCA.

Table 7 – LSI vs. DCA in Historical Bear Markets

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices, PWL Capital Inc.

We again find that LSI produces a better outcome than DCA most of the time in most countries in the sample. Aetna employees and retirees should note that the US experience is significantly impacted by the enormous volatility and seemingly perpetual market drops in the 1930s. We find that, on average, LSI beats DCA by a 10-year annualized 0.25% when the investment period begins with the month after a drop of 20% or more has occurred. Echoing the experience of the full data series we also see that there has historically been more to gain from LSI in the 90th percentile of outcomes than there has been to lose in the 10th percentile. DCA is not offering protection from bad outcomes without also exposing us to a greater risk of missing good outcomes.

Table 8 – Difference in Annualized Returns Starting at Bear Markets (LSI – DCA)

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices, PWL Capital Inc.

It's important for Aetna employees to keep in mind that our trigger to begin the investment period is a 20% drop. In some cases, a 20% drop is followed by more drops, while in other cases it is followed by a rebound. Based on the data in Tables 7 and 8 we can see that rebounds are more impactful, on average than further drops. This results in LSI delivering a better result than DCA most of the time, even during periods of market volatility.

When Stock Prices Are High What You Can Do With Dca

In bear markets prices falls due to increased uncertainty, causing concern for investors deploying new cash. High prices can similarly make investors uneasy for fear of investing at a peak. To observe the relationship between market valuations and the relative performance of LSI and DCA we use the monthly Shiller CAPE ratio. Based on data availability we only observe US stock data. We will define expensive as the Shiller CAPE being in the 95th percentile of all historical monthly observations (February 1872 – May 2020). Comparing LSI to DCA when the market is in its 95th percentile of expensiveness, LSI beats DCA 54.24% of the time.

Table 9 – LSI vs. DCA when Stock Prices are High Relative to all History

Data source: Dimensional Returns Web, CRSP, Barclays Research, PWL Capital Inc.

While it may seem concerning, this observation suffers from a massive bias: at any point in time we do not have the full set of past and future Shiller CAPE data to base a decision - we only have past data in our possession. We adjust for this by measuring the market’s expensiveness only relative to historical data for each data point. For example, for January 1926 we are comparing the Shiller CAPE to the set of data from February 1872 to January 1926, not from February 1872 to May 2020 to test for expansiveness. In this case, LSI beats DCA 63.70% of the time.

Table 10 – LSI vs. DCA when Stock Prices are High Relative to Backward-looking History

This exercise is to remind Aetna employees and retirees that while valuations may look high at a point in time, they can always get higher. Japan might be a particularly interesting case study on the usefulness of market valuations in making the LSI vs. DCA decision. We have less data for Japan, so instead of comparing historical Japanese data, we will compare Japanese valuations to US data to determine expensiveness. The highest level of the monthly Shiller CAPE for the full US historical data series is 44.19 which occurred in December 1999. Japan exceeded this level in May 1986 with a Shiller CAPE of 44.31. While the Japanese market did eventually crash in 1990, there are 29 monthly observations following May 1986 where LSI beats DCA by a wide margin. Even starting in November 1988, with a Shiller CAPE of 72.07, LSI beats DCA in Japan in terms of 10-year annualized returns.

It is well-known that future returns tend to be relatively low when valuations are relatively high. Despite this, using valuation as a signal to time the LSI vs. DCA decision has historically resulted in unfavorable outcomes most of the time.

Cognitive Threats

Despite the statistical evidence in favor of LSI, there is a meaningful psychological risk to investing in a lump sum. For many Aetna investors, losing money in the stock market is psychologically, and in some cases physiologically painful. There is evidence from behavioral finance suggesting that acts of commission are more painful than acts of omission. Making the decision to buy stocks today is an act of commission while deciding not to buy stocks is an act of omission. Buying stocks on a given day and then watching them fall is more psychologically painful than not buying stocks and watching them rise, even if the economic impact is identical. DCA could be viewed as diversifying acts of commission over time to reduce the potential for a psychologically painful outcome.

If DCA seems like a solution to avoiding pain when investing new money, we think that it is a reasonable strategy. However, we also think that if the fear of loss is so great that DCA needs to be employed to make an asset allocation decision palatable, that asset allocation may be too aggressive. It should feel comfortable to invest a lump sum in a risk-appropriate portfolio. We do not want to imply that DCA should never be employed, but we do believe that if it feels necessary to use DCA in order to implement an asset allocation decision, it may be wise to revisit the portfolio altogether.

In Conclusion

Dollar-cost averaging is the decision to gradually deploy a lump sum of cash into the stock market in order to avoid ex-post regretful timing. We have shown that, on average, dollar-cost averaging consistently trails lump sum investing about two-thirds of the time. This is true across stock markets and throughout history, and it is consistent with the historical nature of the equity risk premium. The implicit historical cost of dollar-cost averaging has been an annualized 0.38% over 10 years when compared to investing a lump sum.

When lump sum investing has historically delivered its worst outcomes dollar-cost averaging has looked better than average, but it has not been a consistent remedy. It is not possible to know when lump sum investing will deliver its worst outcomes ahead of time, so we test two forward-looking measures.

We find poor results for dollar-cost averaging during bear markets and when stock prices are high. Dollar-cost averaging tends to underperform lump sum investing during bear markets (53.66% of the time) and when stocks are trading in the 95th percentile of historical valuations (63.70% of the time).

It's important for Aetna employees to note that given the data that supports lump sum investing, we believe that there is a strong statistical argument to avoid dollar cost averaging unless it is absolutely necessary from a psychological perspective, and if that is the case, we believe that the long-term asset allocation may need to be revised toward a more conservative portfolio.

About The Retirement Group

The Retirement Group is a nation-wide group of financial advisors who work together as a team.

We focus entirely on retirement planning and the design of retirement portfolios for transitioning corporate employees. Each representative of the group has been hand selected by The Retirement Group in select cities of the United States. Each advisor was selected based on their pension expertise, experience in financial planning, and portfolio construction knowledge.

TRG takes a teamwork approach in providing the best possible solutions for our clients’ concerns. The Team has a conservative investment philosophy and diversifies client portfolios with laddered bonds, CDs, mutual funds, ETFs, Annuities, Stocks and other investments to help achieve their goals. The team addresses Retirement, Pension, Tax, Asset Allocation, Estate, and Elder Care issues. This document utilizes various research tools and techniques. A variety of assumptions and judgmental elements are inevitably inherent in any attempt to estimate future results and, consequently, such results should be viewed as tentative estimations. Changes in the law, investment climate, interest rates, and personal circumstances will have profound effects on both the accuracy of our estimations and the suitability of our recommendations. The need for ongoing sensitivity to change and for constant re-examination and alteration of the plan is thus apparent.

Therefore, we encourage you to have your plan updated a few months before your potential retirement date as well as an annual review. It should be emphasized that neither The Retirement Group, LLC nor any of its employees can engage in the practice of law or accounting and that nothing in this document should be taken as an effort to do so. We look forward to working with tax and/or legal professionals you may select to discuss the relevant ramifications of our recommendations.

Throughout your retirement years we will continue to update you on issues affecting your retirement through our complimentary and proprietary newsletters, workshops and regular updates. You may always reach us at (800) 900-5867.

Sources

- Constantin ides, George, (1979), A Note on the Suboptimality of Dollar-Cost Averaging as an Investment Policy, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 14, issue 2, p. 443-450.

- Shtekhman, Anatoly, Tasopoulos, Christos, and Wimmer, Brian, (2012), Dollar-cost averaging just means taking risk later, Vanguard Research

How does Aetna Inc.'s frozen pension plan affect employees' eligibility for benefits, and what specific criteria must current employees meet to qualify for any benefits from the Retirement Plan for Employees of Aetna Inc.?

Eligibility for Benefits: Aetna Inc.'s pension plan has been frozen since January 1, 2011, meaning no new pension credits are accruing. Employees who were participants before this date remain eligible for benefits but cannot accrue additional pension credits. To qualify for benefits, participants need to have been vested, which generally occurs after three years of service(PensionSPD).

In what ways can employees at Aetna Inc. transition their pension benefits if they leave the company, and what implications does this have for their tax liabilities and retirement planning?

Transitioning Pension Benefits: If employees leave Aetna, they can opt for a lump-sum distribution or an annuity. Employees can roll over their lump-sum payments into an IRA or other tax-qualified plans to avoid immediate taxes. However, direct rollovers must follow the tax-qualified plan's rules. If not rolled over, employees are subject to immediate tax and potential penalties(PensionSPD).

What steps should an Aetna Inc. employee take if they become disabled and wish to continue receiving pension benefits, and how does the company's policy on disability impact their future retirement options?

Disability and Pension Benefits: Employees who become totally disabled and qualify for long-term disability can continue participating in the pension plan until their disability benefits cease or employment is terminated. No additional pension benefits accrue after December 31, 2010, but participation continues under the plan until employment formally ends(PensionSPD).

Can you explain the implications of the plan amendment rights that Aetna Inc. retains, particularly concerning any potential changes in the pension benefits and what this could mean for employee planning?

Plan Amendment Rights: Aetna reserves the right to amend or terminate the pension plan at any time. If the plan is terminated, participants will still receive benefits accrued up to the date of termination, protected by ERISA. Any future changes could impact employees' planning and retirement options(PensionSPD).

How does the IRS's annual contribution limits for pension plans in 2024 interact with the provisions of the Retirement Plan for Employees of Aetna Inc., and what considerations should employees keep in mind when planning their retirement contributions?

IRS Contribution Limits: The IRS sets annual contribution limits for pension plans, including defined benefit plans. In 2024, employees should ensure that their pension contributions and tax planning strategies align with these limits and the provisions of Aetna's pension plan(PensionSPD).

What are the options available to Aetna Inc. employees regarding pension benefit withdrawal, and how can they strategically choose between a lump-sum distribution versus an annuity option?

Withdrawal Options: Aetna employees can choose between a lump-sum distribution or various annuity options when withdrawing pension benefits. The lump-sum option allows for immediate access to funds, while annuities provide monthly payments over time, offering a more stable income stream(PensionSPD).

How does Aetna Inc. ensure compliance with ERISA regulations concerning the rights of employees in the retirement plan, and what resources are available for employees to understand their rights and claims procedures?

ERISA Compliance: Aetna complies with ERISA regulations, ensuring employees' rights are protected. Resources are available through the Plan Administrator and myHR, providing information on claims procedures, plan rights, and how to file appeals if necessary(PensionSPD).

What documentation should employees of Aetna Inc. be aware of when applying for their pension benefits, and how can they ensure that they maximize their benefits based on their years of service?

Documentation for Benefits: Employees should retain service records and review their benefit statements to ensure they receive the maximum pension benefits. They can request additional documents and assistance through myHR to verify their years of service and other relevant criteria(PensionSPD).

How do changes in interest rates throughout the years affect the annuity payments that employees at Aetna Inc. might receive upon retirement, and what strategies can they consider to optimize their retirement income?

Impact of Interest Rates on Annuities: Interest rates significantly affect annuity payments. Higher interest rates increase the monthly annuity amount. Employees should consider the timing of their retirement, especially at the end of the year, when interest rates for the following year are announced(PensionSPD).

If employees want to learn more about their pension options or have inquiries regarding the Retirement Plan for Employees of Aetna Inc., what are the best channels to contact the company, and what specific resources does Aetna provide for assistance?

Contact for Pension Inquiries: Employees can contact myHR at 1-888-MY-HR-CVS (1-888-694-7287), selecting the pension menu option for assistance. Aetna also provides detailed resources through the myHR website, helping employees understand their pension options and benefits(PensionSPD).

Additional Articles

Check Out Articles for Aetna employees

-

-

Corporate Employees: 8 Factors When Choosing a Mutual Fund -

Use of Escrow Accounts: Divorce -

-2.png?width=300&height=200&name=office-builing-main-lobby%20(52)-2.png)

Medicare Open Enrollment for Corporate Employees: Cost Changes in 2024! -

Stages of Retirement for Corporate Employees -

7 Things to Consider Before Leaving Your Company -

How Are Workers Impacted by Inflation & Rising Interest Rates? -

Lump-Sum vs Annuity and Rising Interest Rates -

Internal Revenue Code Section 409A (Governing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans) -

Corporate Employees: Do NOT Believe These 6 Retirement Myths! -

401K, Social Security, Pension – How to Maximize Your Options -

Have You Looked at Your 401(k) Plan Recently? -

11 Questions You Should Ask Yourself When Planning for Retirement -

.webp?width=300&height=200&name=office-builing-main-lobby%20(27).webp)

Worst Month of Layoffs In Over a Year!

-

Corporate Employees: 8 Factors When Choosing a Mutual Fund -

Use of Escrow Accounts: Divorce -

-2.png?width=300&height=200&name=office-builing-main-lobby%20(52)-2.png)

Medicare Open Enrollment for Corporate Employees: Cost Changes in 2024! -

Stages of Retirement for Corporate Employees -

7 Things to Consider Before Leaving Your Company -

How Are Workers Impacted by Inflation & Rising Interest Rates? -

Lump-Sum vs Annuity and Rising Interest Rates -

Internal Revenue Code Section 409A (Governing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans) -

Corporate Employees: Do NOT Believe These 6 Retirement Myths! -

401K, Social Security, Pension – How to Maximize Your Options -

Have You Looked at Your 401(k) Plan Recently? -

11 Questions You Should Ask Yourself When Planning for Retirement -

.webp?width=300&height=200&name=office-builing-main-lobby%20(27).webp)

Worst Month of Layoffs In Over a Year!

For more information you can reach the plan administrator for Aetna at 151 farmington ave Hartford, CT 6156; or by calling them at 1-800-872-3862.

*Please see disclaimer for more information

Relevant Articles

Check Out Articles for Aetna employees

-

-

Corporate Employees: 8 Factors When Choosing a Mutual Fund

Corporate Employees: 8 Factors When Choosing a Mutual Fund

-

Use of Escrow Accounts: Divorce

Use of Escrow Accounts: Divorce

-

-2.png) Medicare Open Enrollment for Corporate Employees: Cost Changes in 2024!

Medicare Open Enrollment for Corporate Employees: Cost Changes in 2024!

-

Stages of Retirement for Corporate Employees

Stages of Retirement for Corporate Employees

-

7 Things to Consider Before Leaving Your Company

7 Things to Consider Before Leaving Your Company

-

How Are Workers Impacted by Inflation & Rising Interest Rates?

How Are Workers Impacted by Inflation & Rising Interest Rates?

-

Lump-Sum vs Annuity and Rising Interest Rates

Lump-Sum vs Annuity and Rising Interest Rates

-

Internal Revenue Code Section 409A (Governing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans)

Internal Revenue Code Section 409A (Governing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans)

-

Corporate Employees: Do NOT Believe These 6 Retirement Myths!

Corporate Employees: Do NOT Believe These 6 Retirement Myths!

-

401K, Social Security, Pension – How to Maximize Your Options

401K, Social Security, Pension – How to Maximize Your Options

-

Have You Looked at Your 401(k) Plan Recently?

Have You Looked at Your 401(k) Plan Recently?

-

11 Questions You Should Ask Yourself When Planning for Retirement

11 Questions You Should Ask Yourself When Planning for Retirement

-

.webp) Worst Month of Layoffs In Over a Year!

Worst Month of Layoffs In Over a Year!

-

Corporate Employees: 8 Factors When Choosing a Mutual Fund

Corporate Employees: 8 Factors When Choosing a Mutual Fund

-

Use of Escrow Accounts: Divorce

Use of Escrow Accounts: Divorce

-

-2.png) Medicare Open Enrollment for Corporate Employees: Cost Changes in 2024!

Medicare Open Enrollment for Corporate Employees: Cost Changes in 2024!

-

Stages of Retirement for Corporate Employees

Stages of Retirement for Corporate Employees

-

7 Things to Consider Before Leaving Your Company

7 Things to Consider Before Leaving Your Company

-

How Are Workers Impacted by Inflation & Rising Interest Rates?

How Are Workers Impacted by Inflation & Rising Interest Rates?

-

Lump-Sum vs Annuity and Rising Interest Rates

Lump-Sum vs Annuity and Rising Interest Rates

-

Internal Revenue Code Section 409A (Governing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans)

Internal Revenue Code Section 409A (Governing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans)

-

Corporate Employees: Do NOT Believe These 6 Retirement Myths!

Corporate Employees: Do NOT Believe These 6 Retirement Myths!

-

401K, Social Security, Pension – How to Maximize Your Options

401K, Social Security, Pension – How to Maximize Your Options

-

Have You Looked at Your 401(k) Plan Recently?

Have You Looked at Your 401(k) Plan Recently?

-

11 Questions You Should Ask Yourself When Planning for Retirement

11 Questions You Should Ask Yourself When Planning for Retirement

-

.webp) Worst Month of Layoffs In Over a Year!

Worst Month of Layoffs In Over a Year!

/General/General%205.png?width=1280&height=853&name=General%205.png)